Every year on November 10th, I listen to Gordon Lightfoot.

Now as the son of a self declared parrot-head (a Jimmy Buffett fan), Lightfoot has always been a staple, heavy in the rotation. But every year on November 10, I take six minutes or so out of my day to listen to The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

The song, intuitively, is the story of the S.S Edmund Fitzgerald, a freighter which sank carrying a load of iron ore on Lake Superior on November 10, 1975. Its final resting place, Lake Superior, is the world’s largest freshwater lake by surface area of 82,100 km squared, and the 37th deepest lake in the world at a maximum depth of over 400 m. The shipwreck tragically killed all those aboard.

The song is sad, beautifully written and preformed, and more than a little haunting, describing the final day on earth for the 29 aboard.

Now, I’ve been to Lake Superior, a truly beautiful experience, but aside from that I don’t have any personal connection to the tragedy. And yet I have this tradition of listening to Lightfoot tell the tale on the anniversary of the sinking, why?

It just feels like the right thing to do.

By Greenmars – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27927902

So why am I talking about this song and this shipwreck.

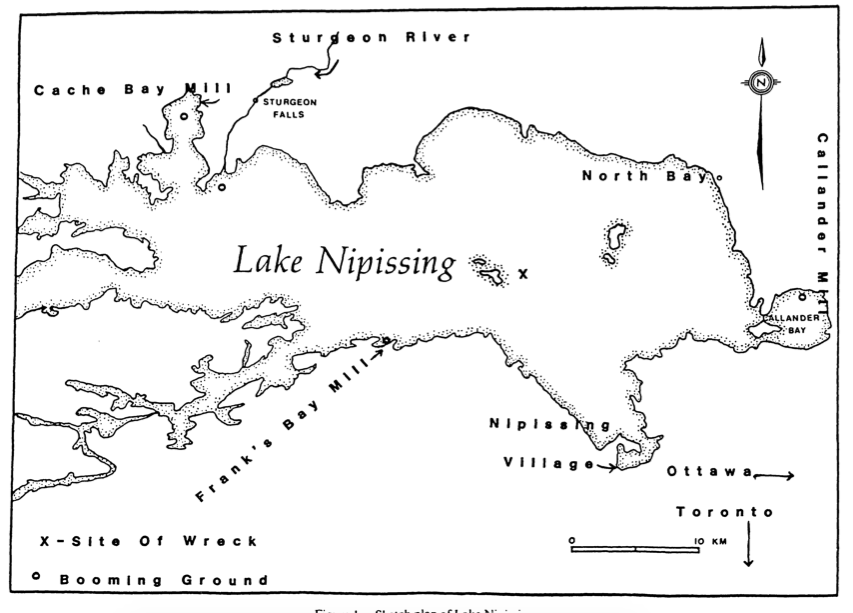

While the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald sits beneath 160 metres of cold Lake Superior water, a mere 14 metres below the surface of our own lake, lies the wreck of Lake Nipissing worst tragedy (Mackey, 2001).

Lake Nipissing’s Steamboats

While steamboats had been an important part of waterways in British North America, later Canada, for the bulk of the 19th century, the steamships didn’t appear on Lake Nipissing until about 1881, as the Canadian Pacific Railway reached the shores (Canadian Encyclopedia, 2017). With the new connection to the far more populous south, the steamship became an important transportation method for the area’s rich natural resources, which the area’s pioneers were beginning to exploit.

The ships brought crucial supplies and personnel to hunting and logging camps in the area, and hauled timber to local mills and railway junctions on the way to southern markets. The steamship era for the lake was an important part of the areas history, as transportation for loggers and settlers was crucial in the establishment and development of the area given the heavy reliance on the primary industries. The era peaked in the roaring ’20s, and ended as diesel engines replaced steam propelled ones (Canadian Encyclopedia, 2017).

The John B Fraser

Alexandre Fraser, owner of the Alexandre Fraser Lumber company, built the 100 foot long John B. Fraser in 1888 in Sturgeon Falls for the purpose of aiding the transport of timber and loggers in his operation. The vessel was named after his brother, John Fraser, with whom he profited from harvesting the McGillivray Lake timber limits. After just a few years of service on the lake, Alex sold the ship to Davidson, Hayes and Company in 1892, a lumber company from Toronto operating in the Lake Nipissing watershed (Mackey, 2001).

From Price (1984). History of the Corporation of Westmeath Township.

The following season, in 1893, went according to plan, until the final voyage of the year that is, on November 8, when approximately 6 crew members were to bring the 20 or so lumberjacks and supplies to a hunting camp (Mackey, 2001).

At around the hour and a half mark of the journey, in the centre of the lake, tragedy arrived with a fury.

Lake Nipissing’s Greatest Tragedy

In the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, Lightfoot sings:

“Does any one know where the love of God goes

Gordon Lightfoot, The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

When the waves turn the minutes to hours?”

A reference to the fact that in Lightfoot’s imagining of the tragedy, the severity of waves and winds made minutes feel like hours for those aboard. The panic of trying to survive the storm, and the tedium of avoiding being swept overboard must have been excruciating. In these situations, time dilates, and slows down. The drawn out process of the shipwreck must have been absolute hell, and the experience probably felt much longer than it was.

In the opposite fashion, it seems with the case of the wreck of the John B. Fraser, the rapidness of the event spelled the tragedy.

Photo: Callander Bay Heritage Museum

By the time the fireman aboard the John Fraser, John Adams, noticed the smoke from the engine room, the room was engulfed in flames. The smoke and extreme heat (temperatures estimated at around 1,100 ˚C) prevented Adams from stopping the fire, or really intervening at all. While the captain ordered for the ships engine to be stopped, the engineer was unable to reach the lever, and Adams believed he never made it out of the furnace room. Thus, the boat continued forward while the passengers and crew abandoned ship (Mackey, 2001).

The ship burned quickly, and men dove overboard into the waters of Lake Nipissing. The scow that the Ship was towing supplies on was adopted as a life boat by a few lucky survivors. Adams was thrown from the ship and with some struggle reached the scow, where four men pulled him aboard. He then used his pocketknife to sever the tie of their craft to the John Fraser (Buffalo Evening News, 1893). Here’s Adams telling his story on the Buffalo Evening News a few days letter:

“I jumped for the stern, but at that moment the boat drifted under the still rapidly revolving wheel and dipped down under the blow, throwing the whole of us into the water. I went down, it seemed almost to the bottom, and as I dropped I got a kick in the face from some one’s boot … When I came up I saw the fellows struggling about in all directions … I was about exhausted but managed to catch a bowline and hauled myself along to a scow in tow of the steamer … As soon as I could pull myself together I got out my knife and cut the towrope and she lay to awhile while we rescued two men. All the other poor fellows had gone under.”

Crew Member John Adams, Buffalo Evening News November 10, 1893

The ship came to rest on the floor of Lake Nipissing, in the middle of the lake adjacent to Goose Islands.

Interestingly, the poor record keeping of the time means that the casualty numbers are estimates, and they have varied over time. Initial stories claimed 18 perished (Buffalo Evening News, 1893), then 19 (Buffalo Enquirer, 1893). Later stories claim 13 of the 17 on board died (Toronto Star, 1972), and the local plaque commemorating the tragedy claims somewhere between 12 and 15 men died (City of North Bay, 2020). Regardless, we know that relatively few on board survived, and that the destruction caused by the fire happened quickly, reducing the potential for mitigating response.

Families of the victims did their part to recover the remains. The following year, the Murray family hired a steamboat to help recover their son Tom’s body from the scene of the wreck. They actually recovered his remains and those of two more victims, bringing closure to the families.

Others, like victim Johnny Smalls’ wife to be, did not find such closure. It is said she walked the beaches of Lake Nipissing for days after the accident, hoping to find any trace of her fiancé Johnny (Mackey, 2001).

Unearthing the Wreck

In 1972, the Aqua Jets Diving Club found the wreck. The Club didn’t have the financial means to remove the ship from its resting place, though the story of club’s discovery did make an appearance in the Toronto Star (Toronto Star, August 15, 1972). Later Nipissing University Archaeologist and Outdoor Education Specialist, Bessel VandenHazel examined the wreck as part of the University’s Underwater Archaeology Project, eventually publishing the results of his underwater excavation as The “John Fraser” Story: An Investigation of the Remains of the Side Paddlewheel Steamer “John Fraser”.

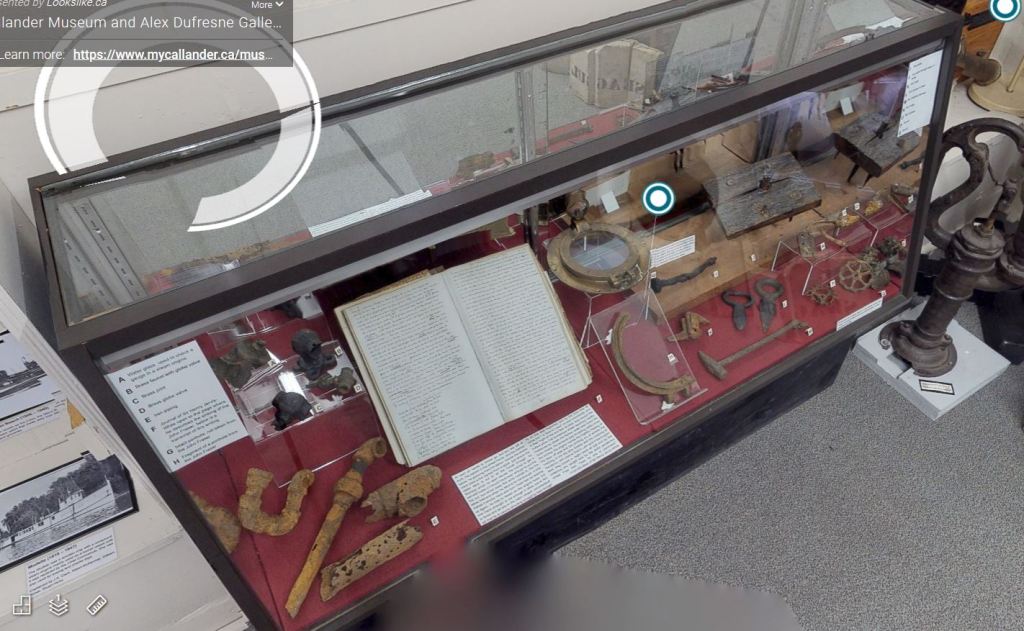

The Callander Bay Heritage Museum hosts most of the artifacts recovered from the ship, including the ship’s steam-whistle. They can be seen on the museum’s virtual tour, and they were kind enough to send me some photos on their display for the John Fraser.

Some artifacts from the wreck can also be found at the North Bay Museum. Some even claim the artifacts are haunted, or are influenced by the presence of the loggers’ lost spirits, with unexplained occurrences by the exhibit. Staff and patrons have claimed things on adjacent walls have fallen without reason, and have witnessed the model train, that runs around the ceiling of the building, stop dead in its tracks right above the exhibit (Maitland, 2018).

Whether the artifacts are haunted or possessed, the wreck of the John Fraser is the deadliest disaster Lake Nipissing has ever seen, and there is little doubt the memory of the catastrophe haunted the regions residents for years.

Searching for Answers

“As the big freighters go, it was bigger than most

with a crew and a captain well seasoned”

Gordon Lightfoot, The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

In the Edmund Fitzgerald case, some have theorized complacency may have been a factor in the deadly accident, with an experienced captain who had travelled boldly through many storms in the past. The theory being that this complacency lead to poor reaction time and ill-advised decision making (USCG, 1977).

In the case of the John Fraser, I can’t help but wonder if the deadliness might also have been the result of a type of complacency.

Lake Nipissing is notoriously shallow and I’m sure the notion that the lake would become their final resting place probably seemed incredibly unlikely. The fact the journey was supposed to be the final trip of the season may also point to some complacency, as it’s possible the crew may have let their guard down in terms of safety and procedure given a full season of successful trips.

This relates to the concept of moral hazard where safety precautions, or increased perceptions of safety, lead to more reckless behaviour and decision making. A full season of successful trips would bring a perception of safety, and with that complacency. When you also consider that type 1 (automatic) thinking occurs when tasks are repeated, and complacency can come with that too, this makes even more sense.

The very deadliness of the accident has been sort of a local mystery. The lake is shallow, and most people, hearing that so many perished in the wreck, can’t help but wonder why so few made it out alive.

We can be sure of the fact the wreck was caused by an engine fire, which we know rapidly forced those aboard into the water. This was undoubtedly a factor in the wreck’s deadliness. We can certainly wonder if complacency may have made the situation worse, although we can’t be sure.

We also know that help was slow to reach the wreck. Employees at Smith Lumber on Frank’s Bay, noticing the plumes of smoke over the lake, departed to help the wreck in their sailboat, although the minimal wind meant it took over an hour to reach the victims (Mackey, 2001). By this time, all that could be done was collecting the few men who had made it upon the life boat, the rest, sadly, had drown.

So, next time you walk the beaches of Lake Nipissing, think about the way Johnny Smalls’ fiancé did the same 127 years before you, longing for her lost lover, mourning for her lost lover.

Consider what John Adams must have thought of the lake, watching his peers drowning, only able to save a select few.

Did the way they “one by one, dropped off and went down” haunt him at the very sight of Lake Nipissing’s shallow waters?

Consider the history of the lake, and the ghosts of thousands of voyages and the trees which travelled across it to become the very bones of houses throughout our province.

Finally, next time you look out at Lake Nipissing, consider the fateful day on November 8, 1893, and remember that even the shallowest of lakes can swallow you whole.

RM

If you enjoy The Gateway’s content, follow us on instagram and twitter, or like our facebook page.

If you want to wake up with the latest Gateway content in your inbox, be sure to subscribe!

Sources:

Buffalo Enquirer (1893, November 8). Another Lake Horror.

Buffalo Evening News (1893, November 8). Eighteen Perished.

Buffalo Evening News (1893, November 10). Thrilling Story: The Nipissing Disaster As Told By One Of Its Survivors.

Canadian Encyclopedia (2017). Lake Nipissing.

City of North Bay (2020). Commerce on Lake Nipissing. Heritage Plaque.

Doucet & VandenHazel (1988) Simple Technology in the Regulation of a Frontier Industry.

Mackey (2001). Lake Nipissing Steamboat’s Date with Destiny. Past Forward Heritage Perspectives.

Maitland (2018). Is Downtown North Bay Haunted? Northern Ontario Travel.

Toronto Star (1972, August 15). Lake Nipissing Paddlewheeler found by Divers.

United States Coast Guard (1977). Marine Board Casualty Report: SS Edmund Fitzgerald.

I knew nothing about this story. Really interesting read!

LikeLike

John Holman and Joe Barrio were members of the dive team.

LikeLike

Thanks for the insight! Must have been an incredibly interesting experience for them.

LikeLike